I think you are right - the "critical mass" of cyclists sometimes in central London, and sometimes outside central London alters drivers' behavior significantly.

The problem I have with the "safety in numbers" argument is that - unless us cyclists all decide to go everywhere in groups - there will always be times when the roads are under this "critical mass" even in Central London. Then the drivers can revert to type and all the advantages of the "safety in numbers" argument goes out of the window. Clearly getting used to large numbers of cyclists doesn't impact behavior at all times - otherwise cabbies would be the most cycle friendly motorists on the road...

Safety in Numbers takes care of that. Its not about the instantaneous numbers at any time but the effect of numbers in general on driver behavior. If there are few cyclists around in general then coming across one tends to be a surprise followed by "what am I supposed to do". If you are generally meeting and interacting with cyclists day in day out then you come to expect them to be around and are familiar with how to behave. Its not an effect that operates only in rush hour and fades during the evening.

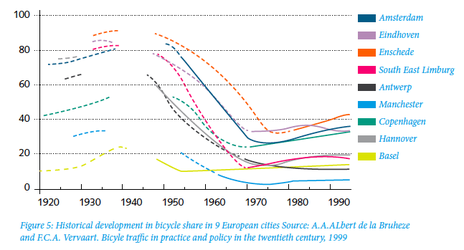

Final question - why do you think cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam have such high modal share if it isn't to do with facilities? Surely it isn't all cultural?

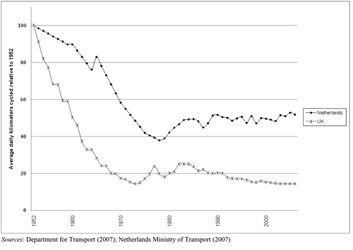

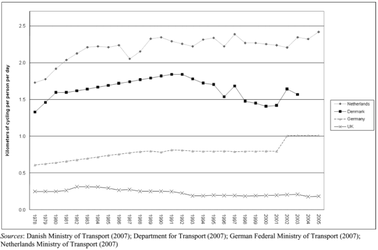

Copenhagen and Amsterdam have high cycling levels because they've always had high cycling levels. The major $1Bn build of cycling facilities in the Netherlands started in the mid 80s and ended in the mid 90s. Cycling levels at the start were high compared to the UK and cycling levels at the end were still roughly the same in both countries. The Louisse study of the results in Delft was summarised by SWOV (the Dutch Institute for Road Safety Research) as follows:

"In the 1990s, Louisse et al. (1994) reported the (second) evaluation of the Delft Bicycle Route Network. This city introduced many bicycle facilities in the 1980s. In 1994 the situation in Delft was again studied, and compared with the evaluation that took place a short time after introduction. There is more bicycle use in Delft than in other medium-sized towns, but this was also the case before the introduction of the bicycle route network. The conclusions in the evaluation study were not very positive: bicycle use had not increased, neither had the road safety. A route network of bicycle facilities apparently has no added value for bicycle use or road safety."

You won't find any mention of facilities other than cycle parking in the Dutch Cycle Balance Audit of cycling provision either and when I asked the person who runs it why not his answer was they were not important.

It is very easy to link the high cycling levels to something superficially attractive as a cause but detailed investigation indicates that it is more coincidence than cause.

I believe the Dutch situation is far more to do with urban planning (distances, convenience), discouraging cars from cities and ensuring cycling is seen as a normal everyday activity